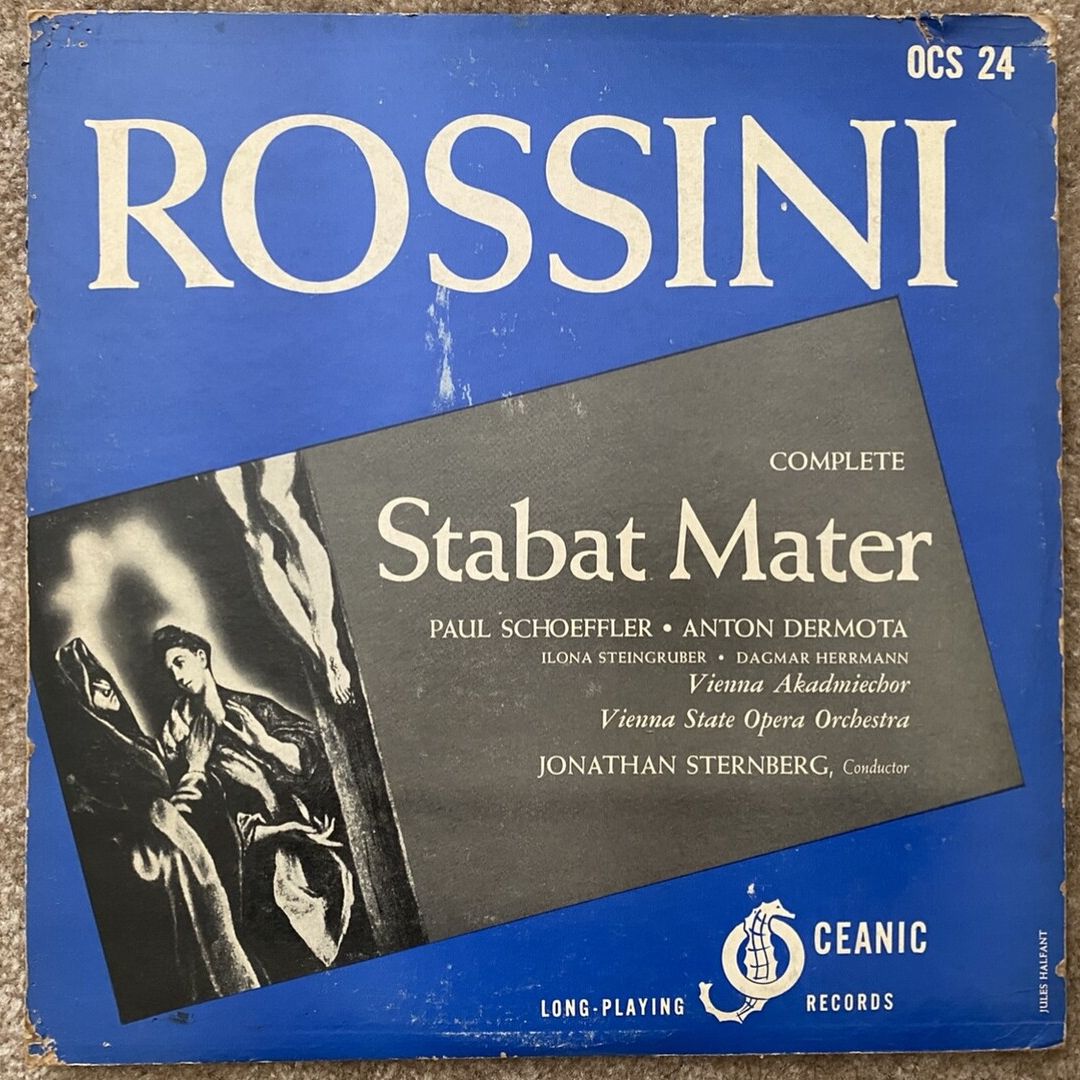

Rossini.Stabat Mater. Vinyl by Oceanic Records 1951

- Foundation date

01 February 1951

ROSSINI. Stabat Mater Complete

Jonathan Sternberg, conductor Vienna State Opera Orchestra 1951

Oceanic Records original Vinyl LP

Alto Vocals – Dagmar Hermann

Bass Vocals – Paul Schöffler

Chorus – Vienna Akademiechor

Soprano Vocals – Ilona Steingruber

Tenor Vocals – Anton Dermota

Cover – Jules Halfant

OCS 24

Copyright 1951 by Oceanic records, NY

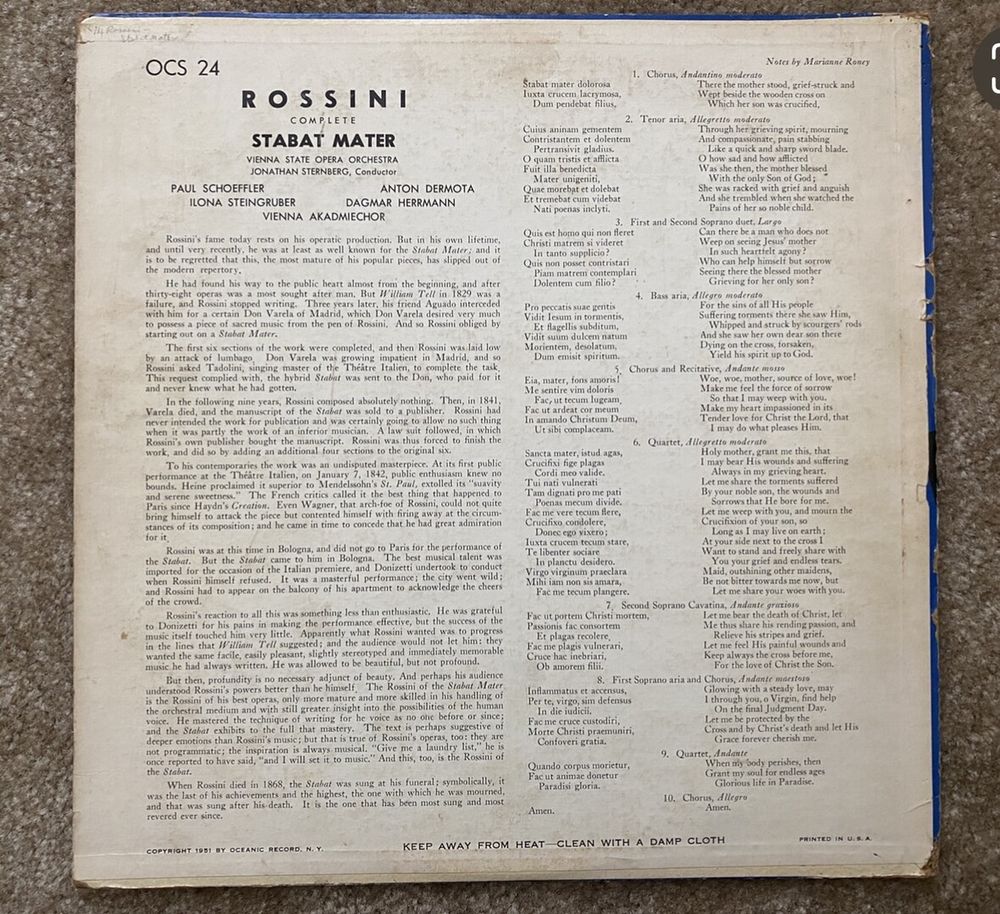

Side1

Introduction Stabat Mater Dolorosa

Cujus Animan Gementem

Quis Est Homo

Pro Peccatis Suae Gentis

Eja Mater, Fons Amoris

Side 2

Sancta Mater, Istud Agas

Fac Ut Portem Christl Mortem

Inflammatus Et Accensus

Quando Cordus Marietur

Finale In Sempiterna Saecula

Rossini's fame today rests on his operatic production. But his lifetime,

and until very recently, he was at least as well known for the Stabat Mater: and it is to be regretted that this, the most mature of his popular pieces, has slipped out of the modern repertory.

He had found his way to the public heart almost from the beginning, and after

thirty-eight operas was a most sought after man. But William Tell in 1829 was a failure, and Rossini stopped writing. Three years later, his friend Aguado interceded with him for a certain Don Varela of Madrid, which Don Varela desired very much to possess a piece of sacred music from the pen of Rossini. And so Rossini obliged by starting out on a Stabat Mater.

The first six sections of the work were completed, and then Rossini was laid low by an attack of lumbago, Don Varela was growing impatient in Madrid, and so Rossini asked Tadolini, singing master of the Théatre Italien, to complete the task. This request complied with, the hybrid Stabat was sent to the Don, who paid for it and never knew what he had gotten.

In the following nine years, Rossini composed absolutely nothing.

Then, in 1841, Valera died, and the manuscript of the Stabat was sold to a publisher. Rossini had never intended the work for publication and was certainly going to allow no such thing when it was partly the work of an inferior musician. A law suit followed, in which Rossini's own publisher bought the manuscript. Rossini was thus forced to finish the work, and did so by adding an additional four sections to the original six.

To his contemporaries the work was an undisputed masterpiece. At its first public performance at the Theatre Italien, on January 7, 1842, public enthusiasm knew no bounds. Heine proclaimed it superior to Mendelssohn's St. Paul, extolled its "suavity and serene sweetness". The French critics called it the best thing that happened to Paris since Haydn's Creation. Even Wagner, that arch-foe of Rossini, could not quite bring himself to attack the pice but contented himself with firing away at the circumstances of its composition: and he came in time to concede that he had great admiration for it.

Rossini was at this time in Bologna, and did not go to Paris for the performance of the Stabat. But the Stabat came to him in Bologna. The best musical talent was imported for the occasion of the Italian premiere, and Donizetti undertook to conduct when Rossini himself refused. It was a masterful performance; the city went wild; and Rosin had to appear on the balcony of his apartment to acknowledge the cheers of the crowd.

Rossini's reaction to all this was something less than enthusiastic. He was grateful to Donizetti for his pains in making the performance effective, but the success of the music itself touched him very little. Apparently what Rossini wanted was to progress in the lines that William Tell suggested; and the audience would not let him: they wanted the same facile, easily pleasant, slightly stereotyped and immediately memorable music he had always written. He was allowed to be beautiful, but not profound.

But then, profundity is no necessary adjunct of beauty. And perhaps his audience understood Rossini's powers better than he himself. The Rossini of the Stabat Mater is the Rossini of his best operas, only more mature and more skilled in his handling of the orchestral medium and with still greater insight into the possibilities of the human voice. He mastered the technique of writing for he voice as no one before or since: and the Stabat exhibits to the full that mastery. The text is perhaps suggestive of deeper emotions than Rossini's music; but that is true of Rossini's operas, too: they are

not programmatic; the inspiration is always musical. "Give me a laundry list,"

he is once reported to have said, "and I will set it to music." And this, too, is the Rossini of Stabat.

When Rossini died in 1868, the Stabat was sung at his funeral; symbolically,

was the last of his achievements and the highest, the one with which he was mourned, and that was sung after his death. It is the one that has been most sung and most revered ever since.